BMI is not perfect

14 Mar 2006I’ve written a post on the BMI (Body Mass Index) of the candidates for Germany’s next Top Model and I have been mentally bugged ever since. Not by images of thin girls, but by the formula of BMI: weight(kg) / length(m) ^ 2 = kg/m².

Why the square of the length?

If the formula were weight/length you can attach a mental image to that: if you took horizontal slices of the body, how much would a 1m high slice weigh? For weight/length³ you can have an image too: kg/m³ or density of the body.

But BMI is kg/m² or something like ‘pressure’ (multiply it with gravity 9.81 m/s² and you get the unit of pressure: Newton/m² or ‘Pascal’).

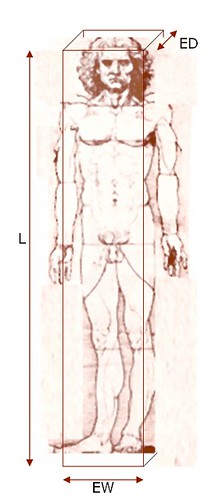

So I started playing with an estimate function for the weight of a person: I modeled a body as a rectangular 3D box.

- The length L is the person’s length.

- The ‘equivalent width’ EW of a body is dependent on the average width (e.g. ear-to-ear, shoulder-to-shoulder, hip-to-hip).

- The ‘equivalent depth’ ED of a body is dependent on the average depth (e.g. tip of the nose-to-back of the head, chest-to-back, tip of the toes to heel).

- The definition of EW and ED is such that L x EW x EW = volume of the body = the actual volume of the body.

- One could calculate that for an ‘ideal’ adult body, e.g. the dimensions of the guy with the arms and legs spread that Leonardo Da Vinci created, EW will be a fraction of the total length, EW = SW x L (SW = scaling of width). One could argue that this SW is dependent on gender, age and race. Let’s ignore that for now.

- Every real person will be less or more wide by a ratio α (if α is < 100% you’re thinner, if it is > 100% you’re wider). Each person will also be less or more ‘deep’ by a ratio β. (if β < 100% you’re thinner, if β > 100% you’re fatter).

- The body has a certain average density (kg/m³), but this will depend on the composition of the body: muscles have a density DM of 1080 kg/m³, fat has DF of only 700-900kg/m³ (less than water: it floats!), bones are more like 2000kg/m³ and lungs will have a totally different density whether they are filled with air or not. I only take into account the % body fat. Let’s call that … λ!

One can expect an obese person to have: a high α (broad hips, thick legs), a high β (fat belly, 4 chins) and a high λ. Since fat weighs less than muscle, one might argue that a high body fat % makes you lighter, but let’s keep in mind that this is mostly excess fat: you still need a minimum of muscles in order to function.

The formula is then:

Weight (kg) = L x (α x EW) x (β x ED) x (λ x DF + (1-λ) x DM)

or

Weight (kg) = L x (α x SW x L) x (β x SD x L) x (λ x DF + (1-λ) x DM)

So the BMI is something like:

BMI(kg/m²) = L x (α x SW) x (β x SD) x (λ x DF + (1-λ) x DM)

which still contains a factor L.

Geometric approach

I discovered in a mailing list dating back to 1996 that I was not the first one to ask this question. It appears that the L² was chosen for empirical reasons: the main puropose of the BMI was to detect risk for obesity and anorexia, and the square happened to match best with clinical statistics.

Dividing the weight by the more intuitive cube of the length L³ can be called the geometric approach. In the formula this gives:

GEO(kg/m³) = ( SW x SD ) x (α x β) x (λ x DF + (1 - λ) x DM)

with SW and SD being constants (be it maybe for a particular gender, race or age). This makes total sense.

Allometric approach

A Michael Raymond Pierrynowski actually argues that to have a more meaningful index, you need to divide by L ^4. This compensates for allometric effects: larger persons/mammals need stronger bones to support all that mass:

One way to observe that geometric similarity is NOT correct is to note that some animals are not scaled up versions of others (i.e. the lion and the cat). The lion has much thicker legs than the cat to support its trunk. These larger legs must have extra mass, therefore doubling the size of the cat does not 8 fold increase the mass of the lion but increases the mass by 16 times.

I took the data I had of the candidates for the Top Model show, and also added statistics for US baseball players (the team from the LA Lakers), who are at the other end of the spectrum. A common criticism on BMI is that it often qualifies athletes of heavy sports like baseball as potentially obese, whil they rather have way more muscles than average people and are often very healthy individuals.

I’ve put 3 lines on the graph for each system: a bottom line, under which you are considered rather light, an average line, and a top line, above which you are ‘too heavy’. You can see that the allometric curves are more lenient on the baseball players. Almost all models as well as all athletes fall within the norm.

Conclusion: BMI is just ‘a’ way of measuring relative weight, maybe not the best. The usage aof the square of the length is contra-intuitive, but seems to give acceptable results.