A Sudoku challenge generator

14 Aug 2006When on holiday, one can kill time solving Sudoku puzzles. When one has done a dozen of those puzzles and one happens to have a wandering mind like mine, one starts wondering how those Sudoku challenges are created, and if it would be possible to describe an algorithm that can make such a scarcely filled-in 9-by-9 grid. Some sunny hours later one has a system that might work (I haven’t implemented it fully yet). For my future reference: here’s how I would do it.

REMARK: this algorithm is quite logical and as such, I seriously doubt I would be the first one to think of it. I can imagine that Sudoku puzzles are already made by the hundreds with a program that uses this or a quite similar system. I’m not claiming it’s an original ‘invention’, just a fun problem to tackle.

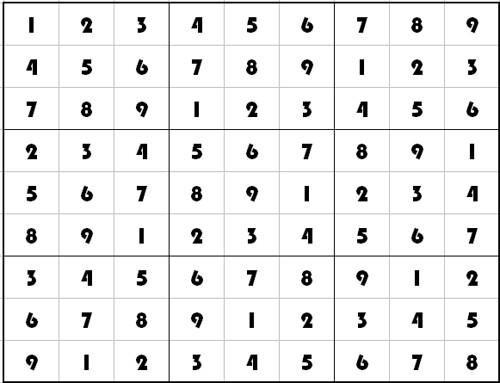

Step 1: take a good root grid

Let’s start with an completely valid Sudoku filled-in grid. Any one would do, I take the one that has 1-2-…-9 in the top row, and in the top left 3×3 square:

If you’re not familiar with these puzzles: for a 9×9 grid to be a valid Sudoku grid, the following 3 requirements should be fulfilled:

- for each row: every number from 1 to 9 should occur exactly once

- for each column: every number from 1 to 9 should occur exactly once

- for each 3×3 square with a thicker border (there are 9 of them): every number from 1 to 9 should occur exactly once

Step 2: shuffle the grid around

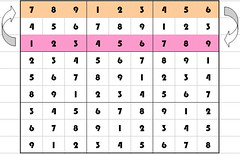

There are a couple of transformations that we can apply on a Sudoku grid while still keeping it in a valid state. They are:

- swapping two rows in same group: when you swap 2 rows within the same ‘group’ (within the 3×3 borders), the Sudoku requirements remain fulfilled (I won’t include a formal proof, but trust me on this one).

- swapping two columns in same group: the vertical version of the previous one.

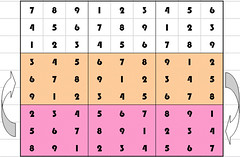

- swapping two groups of rows: when you swap two 9×3 groups of cells, that keeps the grid valid too.

- swapping two groups of columns: vertical version of the previous one

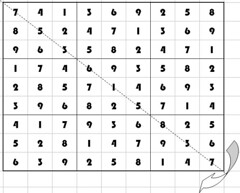

- transposing the whole grid (the columns become the rows and vice versa)

There are maybe other, more complex, transformations, but these will take you a long way. Maybe someone could prove that with these base operations all possible Sudoku grids can be constructed, or maybe on the contrary, that some combinations can never be reached. We don’t really care, as long as we can apply a random sequence of the above transformations to get a grid that seems kind of random but is still valid.

You can compare this ‘shuffling’ with the Rubik cube: you get it in the virgin state and then you shuffle it around to get a pseudo-random start situation.

Step 3: erase a number of cells

This was the more tricky part. How many cells do I erase, and how do I make sure that the remaining challenge is still solvable, with only 1 solution?

- number of cells to erase: this is one of the most important factors that define the difficulty level of a Sudoku puzzle. There are 81 cells in a full grid, the ‘easy’ puzzles have around 30-35 remaining cells, the intermediate 25-30, the difficult ones 20-25. These are indications based on real-life examples, not some kind of official law. One could probably make a 30-cell challenge that is unsolvable, or a 22-cell challenge that is considered ‘easy’. But let’s take these numbers as a guideline

- random approach: just erase 50 (easy) to 60 (difficult) cells at random. Very easy, but it is possible to make grids that are unsolvable. Consider e.g. a challenge with only the bottom 3 rows filled in (i.e. 27 remaining cells). There’s no single solution to that.

- random with simple limits: e.g. take as a limit that only N rows or columns may be empty. Taking N = 0 for easy challenges and N = 1 for difficult challenges could be a safe strategy. I’m not sure this is safe enough, so I made something even more refined.

- random with level-1 check: this would only erase the cell if it could be solved by a level-1 strategy. What do I call “level-1”? That is: if applying the sudoku rules (rows/columns/squares) only leaves 1 possible solution for that cell. To calculate this, you just take the nine possible values for that cell and strike out all numbers that already appear in that row, that column and that square. If you’re left with only one possible number, that’s a level-1 solution.

One remark on this: the first couple of cells you check will always be level-1 solvable (if there are already eight occurences of e.g. ‘5’ in the grid, the ninth is always level-1 solvable). As the grid becomes emptier and emptier, some cells will not meet the level-1 requirement and will not be erased. There is a point somewhere where no more cells can be erased, but I’m not really sure where that point will be, and how variable it is (is it e.g. always between 20 and 30? Is it always 27?) I haven’t built a prototype yet so I can’t say. If this point would be too high (we want to make a ‘difficult’ challenge and we can’t erase any cell anymore to get below 25), we might need a 2nd round of erasing that does not use the level-1 check. - random with level 2 check: level 2 is where you need to make suppositions about a second cell in order to find the solution for the given cell. I’m not going into details (nor do I have all the details 🙂 ).

- row-per-row / column-per-column / square-per-square erasing: instead of jumping at random in the grid, check a (random) cell for each row sequentially, going from 1 to 9 and start over. This can help to make the distribution of remaining cells more even (e.g. every square has 2 – 4 cells left). The ‘simple’ or ‘level-1’ checks can be used like described above

- number-per-number erasing: instead of jumping at random in the grid, check a (random) occurrence for each number sequentially, going from 1 to 9 and start over. This can help to make the distribution of remaining numbers more even. The ‘simple’ or ‘level-1’ checks can be used like described above

The only way to make sure that the resulting algorithm actually works, would be to prove it mathematically (don’t feel that’s something I would want to do – certainly not step 3) or to build a proof of concept and let it run a solid number of test challenges (don’t have that much free time now). If anyone has better suggestions, don’t hesitate to leave a comment.